6

7

Concordia

Merchant Taylors’ School

Being exposed to the elements makes you appreciate how

vulnerable you are. If the weather decides it doesn’t want you to

carry on, you have to listen to it.

Summer

2015

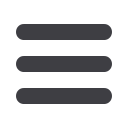

The top of the Tor-Ashuu Pass (3500m elevation), Kyrgyzstan

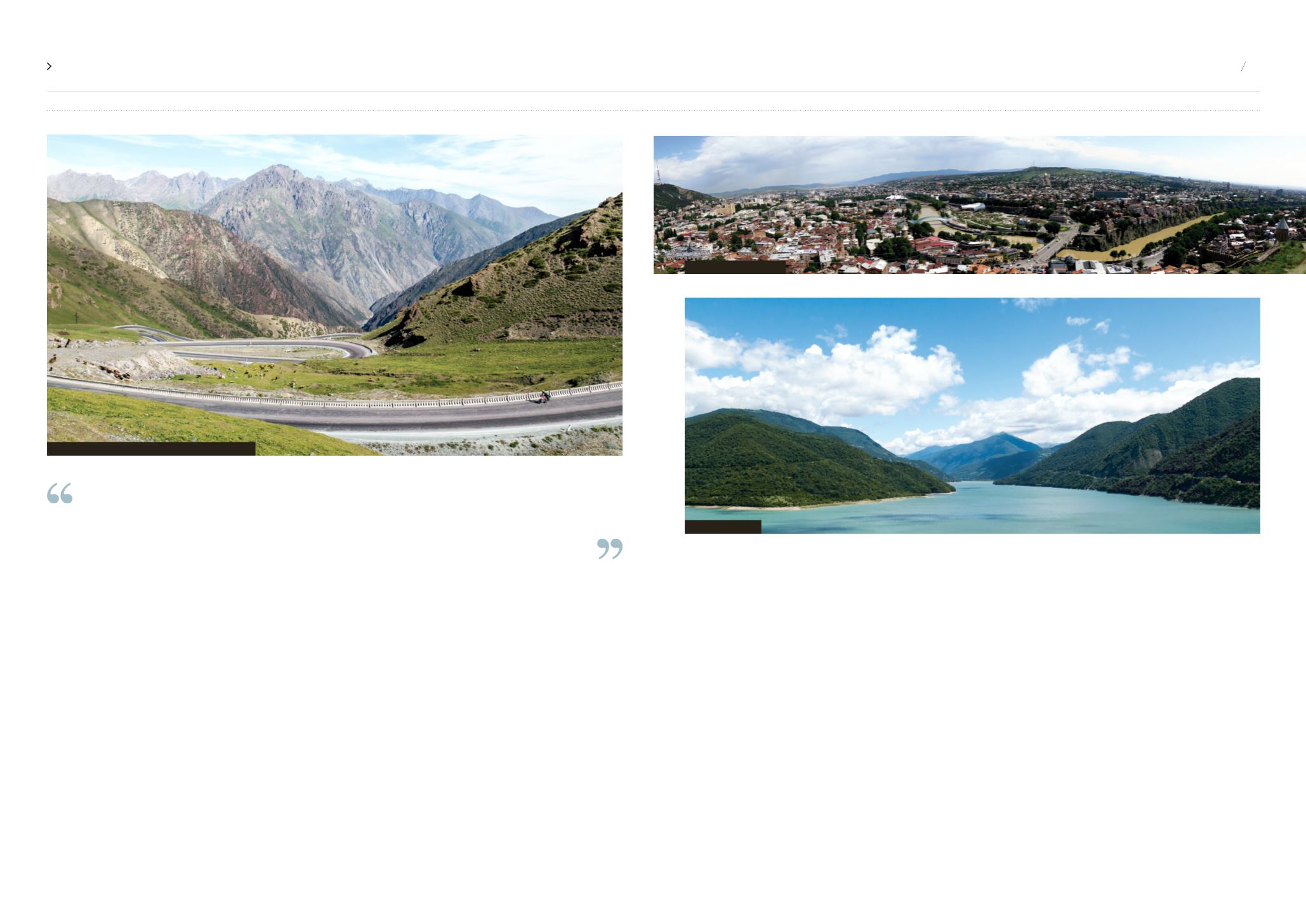

Panoramic of Tbilisi, Georgia

Reservoir in Georgia

Embarrassingly, we failed the first

leg by missing the ferry from Dover,

making us realise this was a marathon,

not a sprint. Only when we reached

Istanbul, after a month on the road, did I

allow myself to think of what lay ahead.

The size of the achievement –

contrasted with the sudden feelings of

“What now?” – meant that each day I

was flooded with conflicting emotions

ranging from elation and euphoria to

sadness and despair.

In the western US, there was a 180-

mile stretch of road (catering for cars)

in the Mojave Desert with one food

and water stop

en route

. We arrived

– the shop was shut. You just have to

dig down.

One late afternoon, in the Caucasus

Mountains in Georgia, a thunderstorm

carrying massive hailstones rolled in. As

bolts of lightning hit the floor around

me I froze – assuming I was going to die

right there. There was nothing I could

do. Shaken up, I just had to plough on

another two kilometres to find shelter –

and Will.

Being exposed to the elements

makes you appreciate how vulnerable

you are. If the weather decides it

doesn’t want you to carry on, you have

to listen to it. In Europe it was rain; in

Asia it was wind.

The direction and force of a wind can

be the difference between crawling to

gain less than 50 miles in a day and

being hoisted for up to 130 miles. Or

being blown off your bike or staying

put. I learnt to embrace the positive and

accept what I couldn’t change.

I had expected the ride to be more

physically demanding but I’d say two–

thirds of the effort was mental. You need

strength to find the drive to get up every

day and sit on a bike for seven hours.

The unpacking and packing of

panniers felt relentless. The monotony

of chunks of the journey was also hard.

In Central Asia we were presented with

the same long straight desert road, with

the same terrain, seven hours a day, for

weeks at a time. Music and podcasts

offered some respite.

Will and I started the trip talking as

we cycled but we ran out of things to

say. Eventually we understood each

other so well, knowing what each other

was thinking, we didn’t need to speak.

Spending every waking moment

with one other person is intense. With

exhaustion, tempers can fray – but you

both know that without the other guy’s

support you are lost.

The trip enabled Will and me to

experience some of the world’s richest

cultures, see its most stunning places,

by riding some of its greatest roads.

Every single day, I’d think: “Wow. Look

at this place.”

The awe-inspiring landscapes along

the back roads of Japan, the mountain

passes of Kyrgyzstan and national parks

in the US made up for any hardship. I’d

reflect: “Look where I am, how did this

happen? How lucky am I?” Thinking

time was something I was never short of.

In mid-December, we finally coasted

to South Beach in Miami. We had

cycled 14,558 miles in 234 days. It felt

weird. I knew I was going to miss the

enthusiasm and excitement that had

lifted me out of my tent every day.

On a par with the incredible scenery,

my biggest takeaway from the trip

was that, without exception, everyone

we met was overwhelmingly friendly,

kind, generous and hospitable. The

experience has been amazingly

humbling. The less people had, the

more willing they were to welcome and

provide for us.

One meeting has particularly stayed

with me. It was late one evening in

Uzbekistan. Will and I were looking for

a patch of land to pitch our tents when

a shepherd appeared from nowhere.

Sussing what we were trying to do, he

helped us find a place to camp. He later

returned, joined by friends, to share a

big flask of tea with bread.

One friend gave Will his hat, which

was pretty much all he had. I often

reflect on meeting these men, as they

were our age. Born under different

circumstances, theirs could have been

my life as well.

Stepping out of the job market for

nearly a year, only five years into my

working life, was a risk. But undertaking

this epic journey was the best decision

I’ve ever made and proving I can do

something if I set my mind to it has

filled me with confidence.

Strangely, I’m now driven by a desire

to fail – or to at least push myself to

discover where my limits lie. I never

want to look back at life and kick myself

for not having taken every opportunity.

If you wish to read more about the trip,

please go to

www.ridingforrhinos.org