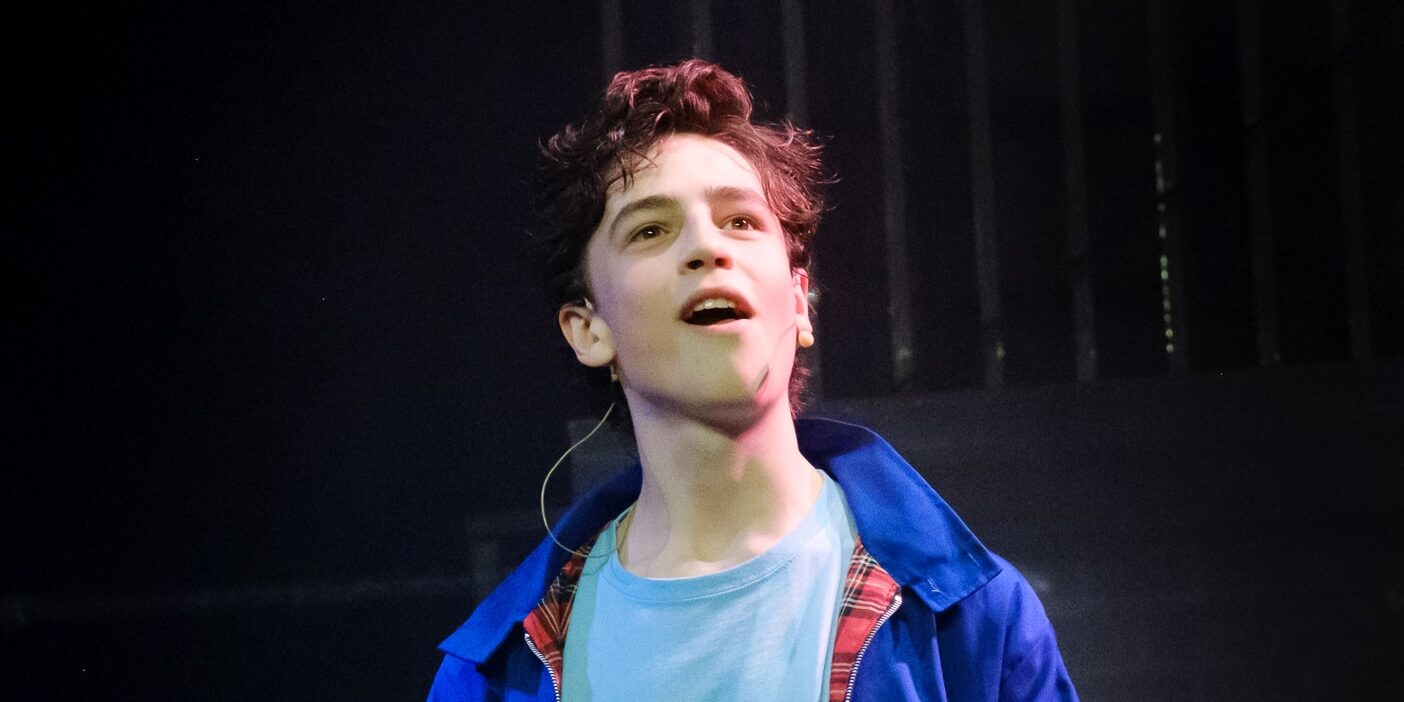

On Thursday 5th June, Lower Sixth English Literature students went to see ‘Giant’, a new Olivier-award winning play by Mark Rosenblatt, at the Harold Pinter Theatre. They are studying the text as part of their A-level Coursework.

Edward G:

In about 5,000 words, Rosenblatt tells you the tale of the downfall of famous childhood author Roald Dahl – and yet you feel like you are eating Hallie’s famous sorbet. In a rather slow first act, Dahl (played by award-winning John Lithgow) is as cool and classy as the complementary ice-cream served at the Harold Pinter Theatre. After the interval, things heat up as Aya Cash, playing New-Yorker Jessie Stone, attempts to force an apology from literal and metaphorical giant Dahl, conjuring up images of dinner-time disputes with the grandparents. Somehow compelling despite shocking antisemitism, like peeling off a hangnail, Rosenblatt picks at the scabs of the Nazi regime and pokes at the raw blister that is Israel’s foreign policy, employing irony and ‘playground xenophobia’ that at times darkly amuses, and at others, horrifies the words-will-never-hurt-me English audience.

Ben K :

1983, sweltering summer’s day, renovations, noise, bad day: this is the setting of Rosenblatt’s cunning new afternoon biography of the one and only Roald Dahl- The Big, not-so friendly, Giant. In a limbo between finishing his new children’s book ‘the witches’ (as well as a suggestively antisemitic review) and receiving his knighthood and getting married, we are shown a glimpse into the capricious yet compassionate mind of the king of children’s literature. As Dahl’s ‘direct’ nature becomes more evident, it feels as though, certainly by the end of the first half, the script is simply a minefield, in which all the audience can do is watch as the characters navigate blindfolded on a pogo stick; as concerning as it is entertaining.

Zak K:

Giant: A sensitive portrayal of a controversial character.

Rosenblatt’s debut play sparks intrigue through the exploration of the overlooked battle between antisemitism and ethical views of infamous children author, Roald Dahl. The brilliant casting of this play, with lead actor John Lithgow perfectly embodying the “giant” albeit frail old man that Dahl was during the time with Timeout magazine describing him as “a walking metaphor: a giant – of literature, of stature – and big.” However, was this “giant” was one of terror, or was he warm and affable?

David A:

If you have a free weekend between now and August and you like theatre, Roald Dahl or even Harry Potter, Giant would be worth a few hours of your time. The irrefutable success of Mark Rosenblatt’s debut play is to have found the space between black and white that is so often shied away from for fear of ‘social media’s retribution’. Sure, he could create a Dahl without defence, removing the implication he was anything but an antisemite, but instead he also showed us the mind that could make the staple of children’s books for decades. By taking the road less trodden, Rosenblatt both creates a drama that leaves you unable to understand your feelings afterwards and highlights the man behind every giant. By this, I mean he shows you the wit and fang-sharp mind of Dahl and then shows you a stubborn child, unable to contain his prejudices against a race of people. I might say you wouldn’t know Dahl was a children’s writer from Lithgow’s venomous characterisation, but then seeing it in action I can’t help slightly agree with Jesse’s (played by Romola Garai) closing jab at him as being a ‘belligerent, nasty child’.

Jonah G:

Mark Rosenblatt’s ‘Giant’ provides an incredibly thoughtful exploration of the line between bigotry and considered opinion. The specifically explosive issue of Israel is the central conflict in this play and Rosenblatt writes without a filter but also with a great deal of nuance and empathy. Jessie Stone, Dahl’s biggest detractor in the play, isn’t a hardlining Zionist. Dahl is presented as is charismatic, forceful and intelligent, brought to life in an Olivier-winning performance by John Lithgow. Rosenblatt masterfully provides arguments from both sides, challenging the views of every audience member simultaneously. We are led, much like the majority of the cast, to see the best in Dahl throughout the play up until this ‘Giant’s’ infamous phone interview, delivered with spiteful glee. Rosenblatt explores our conflation of virtue and talent, bigotry and reason, creating a play which is both moving and disturbing. If you’re going to see it, go in blind- without knowing the content of the interview or book review- and leave shocked, enthralled and (hopefully) with your views challenged and reconsidered.