I recently had an interesting conversation with a pupil about language and long words. That prompted some thoughts and so instead of taking on weighty moral matters, or considering the state of world politics, I want to have some fun this morning and share some thoughts about the English language. We all speak it fluently, but I think there are plenty of wonderful things to discover about it that might surprise you.

Some estimates suggest that English has around 500,000 words that are in general use, compared to 135,000 in German and around 100,000 in French.

It’s one of the reasons that we have a book called a thesaurus to help us navigate them all. For example, English has over 100 different words that could be used instead of the word ‘house.’ All of them carry subtle shades of different meaning. It makes a difference if your home is called a mansion, as opposed to a shack. In French there are around 12 equivalent words.

In addition to having lots of words, English also has approximately 3500 grammatical rules. Many, perhaps even most, of these rules are followed by native speakers without them even realising their doing so. You all have instinctive knowledge of the language, native fluency and unconscious mastery – you don’t even know what you actually do know.

Here are just two examples of that.

Rule 1: the Adjective Order Chain

Imagine describing a pot. You might say, ‘A beautiful, little, antique, oval, yellow, Chinese, porcelain, decorative pot.’ This sounds perfectly normal to the ears of a native speaker, even if it is rather a long and convoluted description. But try saying those adjectives in a different order. For example, let’s try: ‘An oval, yellow, Chinese, porcelain, decorative, little, beautiful, antique pot.’ Suddenly, it feels bizarre – it is very difficult to even bring myself to speak the adjectives in that new order. This is because adjectives in front of a noun must follow a strict law. They must be given in a very specific and unchanging order of categories. The rule is that adjectives should be in this order: opinion, size, age, shape, colour, origin, material, purpose, and then noun.

This is why we say ‘The big brown table’ instead of ‘The brown big table.’ It is because the word ‘big’ (which is in the size category) must come before ‘brown’ (which is in the colour category) in the chain. This is an enormously complex rule, but it is so ingrained that although almost none of us could write the list of categories out in the correct order, I bet every single person in the room is able to use the rule faultlessly and spotted it when I failed to follow the proper order of adjectives.

Rule 2: The Law of I, A, O

Next consider these pairs of words: hip hop, ding dong, ping pong, and tick tock. Why do these combinations sound right, but hop hip, dong ding, and tock tick sound wrong? This is governed by a rule called ablaut reduplication, a form of repetition where a word is repeated but the vowel sound changes. The rule states that when you repeat a word or sound but vary the vowel, the first element must use a higher vowel (formed from the front of the mouth) and the subsequent word element should use a lower vowel (formed further back in the mouth).

Crucially, if there are two words, the first must use an I vowel and the second must use an A, an O or both of them. Examples:

- i → a: zig-zag, mish-mash, snip-snap‑

- i → o: tick-tock, ding-dong, King Kong

- i → a → o: bish-bash-bosh

Although I am fairly confident you have never heard of the grammatical rule of ablaut reduplication, you undoubtedly follow the rule instinctively. You will have always chosen to say clip clop and never clop clip.

This instinctive law that you picked up without even knowing it is immensely powerful. It is so strongly ingrained in you that it can even override the adjective order chain that I described earlier. For example, ‘The big bad wolf’ breaks the adjective order rule I described earlier. In that order, opinion comes before size, so by rights you should say the bad big wolf. But you never do.

It is often said that English is both easy and hard to learn – it actually has relatively simple rules of grammar, despite what we’ve just learned. It has a large number of words that derive from other languages which can make it easier for others to recognise, and our basic sentence structure is often straightforward. On the other hand, there are many exceptions to the way the same words are pronounced in English. English is full of idioms and metaphors, which can put people in a spin. There are lots of irregular verbs and spellings that don’t have a clear pattern which means they just have to be learned. The word ‘misspelt’ can be written and pronounced in two different ways. And there are a wide variety of regional accents and dialects.

There is a wonderful poem that captures the eccentricities of English spelling called The King’s English. I shared it in an assembly a few years ago, but it bears repetition here. Listen to this:

The King’s English

I take it you already know

of tough and bough and cough and dough?

Some may stumble, but not you,

on hiccough, thorough, slough, and through?

So now you’re ready, perhaps,

to learn of less familiar traps?

Beware of heard, a dreadful word,

that looks like beard, but sounds like bird.

And dead – it’s said like bed, not bead;

for goodness’ sake, don’t call it deed!

Watch out for meat and great and threat.

(They rhyme with suite and straight and debt.)

A moth is not a moth in mother,

nor both in bother, broth in brother.

And here is not a match for there,

nor dear and fear, or bear and pear.

And then there’s dose and rose and lose –

just look them up – and goose and choose

And cork and work and card and ward

and font and front and word and sword

And do and go, then thwart and cart:

come, come! I’ve hardly made a start.

A dreadful language? Why man alive!

I’d learned to talk it when I was five.

And yet, to write it, the more I tried,

I hadn’t learned it at fifty-five.

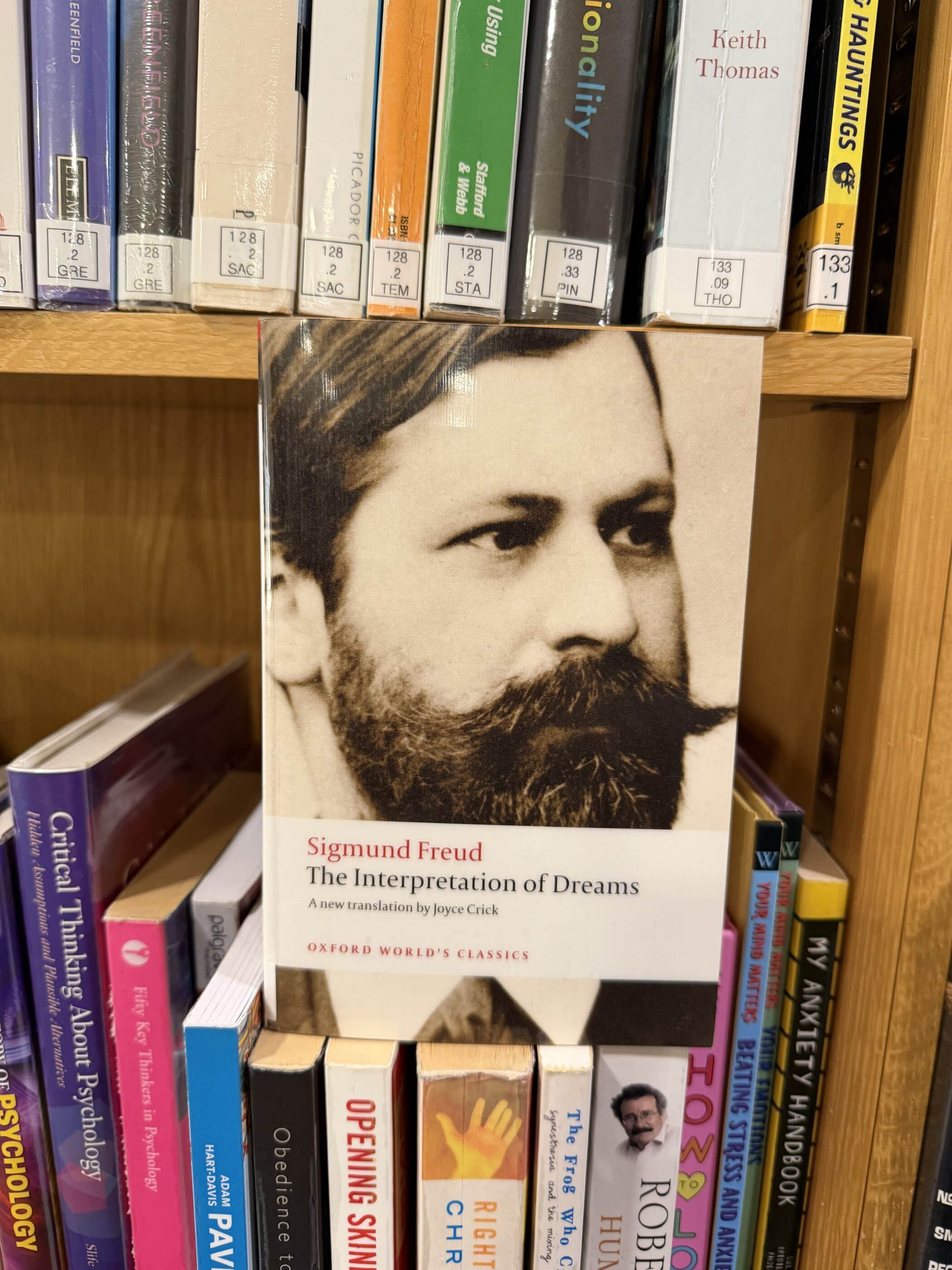

These words are further complicated by their bizarre origins. For example, the course of study that you follow is described by the word ‘syllabus’. ‘Syllabus’ comes from the original Greek word ‘sittybas.’ A bungling scribe once incorrectly copied one of Cicero’s letters and rendered it ‘syllabas’, from which we get the word that describes what you will do all day. Words in English can sometimes just appear. The word ‘dog’ is one of the greatest linguistic mysteries. No-one knows where it came from. It suddenly appeared about a thousand years ago, had no origin from another language and replaced a strong earlier word ‘hund.’ Why? No one knows.

Others are constructed in unusual ways. The word nickname comes from a linguistic mix‑up: it began as ‘an ekename’ (an ‘additional name’ as it comes from the Old English word ‘eac’, meaning also or additional) in about 1300AD. Over time the boundary between the words shifted, turning ‘an ekename’ into ‘a nekename’, and eventually nickname.

Other words you know formed in the same way. The word ‘apron’ was originally ‘a napron’. The word ‘newt’ began as ‘an ewt.’ The ‘n’ can go the other way too. The word ‘umpire’ was originally ‘a noumpere’. Adder came from the Old English ‘a næddre’, which became ‘an adder’.

I could go on, but I had better take a rest. Gaining access to another language, as you do at this school when you study French, German, Spanish, Latin or Greek is like opening a treasure box of wonderful new discoveries. Similarly, we should treasure the fact that we have a command of the English language. We should take the time to appreciate it, even if we do not always fully understand its hidden rules and complexities. I think English is a jewel amongst languages.