I recently bought a Fitbit device. I use it to measure the number of steps I take each day and it is a useful spur to action. However, an unexpected additional feature is that it is able to analyse my sleep patterns. Each morning, I wake up to discover how long I slept and the depth of that sleep. I even find the device says I was awake despite having no memory of this. Sleep is strange. As far as scientists know, every animal must sleep. It clearly plays an essential role in living things, especially as an animal is more vulnerable when asleep. We don’t fully know what sleep offers us; however, whatever it is, evolution has prioritised it over the occasional risk of being eaten.

Sleep in humans is categorised into three types: deep sleep, light sleep and REM sleep. And whilst we sleep, we dream. It seems that humans spend about two hours dreaming per night, and each dream lasts between 5 and 20 minutes. You can dream in any of the sleep types, but it seems that the most vivid dreams and the ones that we are most likely to recall as meaningful take place in REM sleep. Whatever advantage sleeping gives us, it is likely that dreams play a large part in it.

But we know so little about what dreams are and why they are important to us. How strange that an experience so familiar as dreaming should be so mysterious. I bet you can recall a dream you had recently. Dreams can feel very significant. People have had insights and revelations whilst dreaming. Dreams can be uplifting or they can be terrifying.

Everyone knows the soliloquy from Hamlet where he contemplates death. It starts, ‘To be, or not to be, that is the question.’ Not so many remember it goes on

To die, to sleep; To sleep, perchance to dream-ay, there's the rub: For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause.

There are so many questions about dreams, most of which are unanswered. Can you control your dreams – maybe even forcing yourself to wake up? Are dreams meaningful? Do you dream in colour?

What do you think dreams are? Messages from supernatural beings? Indications of anxiety? A message from your subconscious? The first dream we know of falls into one of these categories. There is a surviving letter, written by an Ancient Egyptian man named Hani. He wrote it 4100 years ago, asking for help with terrifying dreams. People are still having anxiety nightmares today. Nothing much changes.

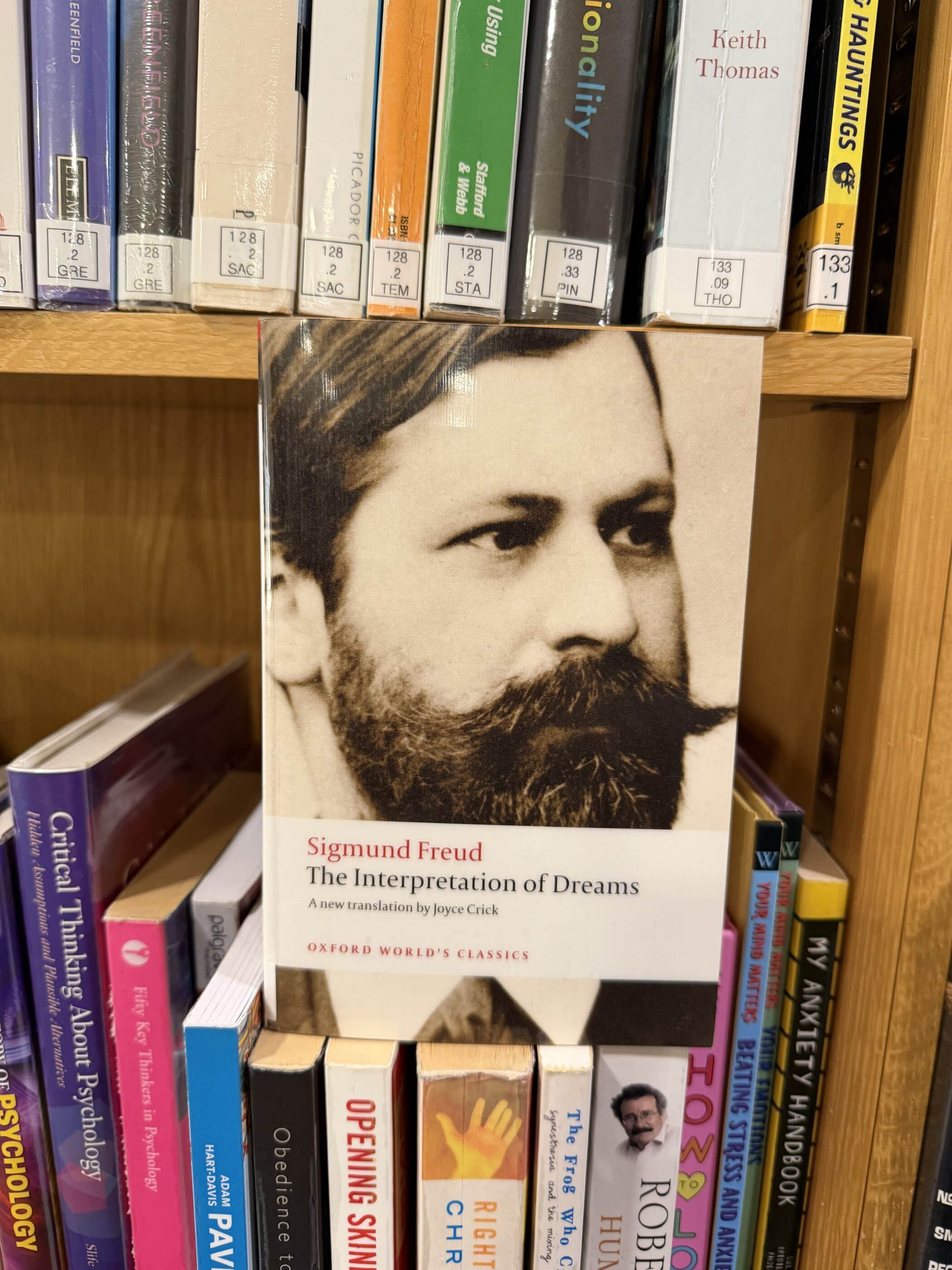

The Ancient Egyptians had professional dream interpreters. We still have them today, but nowadays we call them psychiatrists. Sigmund Freud wrote that dreams are ‘disguised fulfilments of repressed wishes.’ His book, The Interpretation of Dreams, argues that dreams are meaningful expressions of unconscious desires, rooted in repressed wishes, and interpreting them reveals hidden aspects of the mind. He called dreams, ‘The royal road to the unconscious.’

Much of what he thought has been debunked since, but we still think of dreams as a good way to understand ourselves better. Of course, that idea is far older than Freud. Shakespeare makes it a key part of his play Macbeth. You may know the sleepwalking scene, where a sleeping Lady Macbeth reveals her inner thoughts and fears in a terrifying insight into guilt and mental suffering. In the same play, Macbeth describes sleep (which his guilt denies him) beautifully:

Sleep that knits up the ravelled sleeve of care, The death of each day's life, sore labour's bath, Balm of hurt minds, great nature's second course, Chief nourisher in life's feast.

But just how does sleep – or rather dreams – ‘knit up the ravelled sleeve of care’? Science has some answers. The problem is there are too many answers, and they contradict each other. One theory states that dreams could be a way to test how you would respond to scary situations. That might explain those nightmares we all have sometimes. Another theory says they let us address emotions and sadness. Or dreams could be a way to process the information and memories we accumulate over the day. Or they could be a sort of mental random noise, to which we give meaning after the event, once we wake up. Or all of these. Or none. No one knows.

The one I like best is the idea that dreams are our route to creativity. Our own experience, and some scientific data, suggests that we can use our dreams to provide inspiration and insight. The German chemist August Kekulé allegedly discovered the ring structure of benzene after dreaming of a snake biting its own tail. Mendeleev said that he dreamt up the beautifully elegant periodic table in his sleep.

I am not in that league, but just before falling asleep I have found it useful to think about a difficult problem that needs to be fixed. I have often found that I wake up with a solution, having mulled it subconsciously in my sleep. John Steinbeck, the novelist, did the same. He wrote, ‘A problem difficult at night is resolved in the morning after the committee of sleep has worked on it.’ So, my favourite theory to explain the importance of dreams is they could be there to allow us to make unexpected connections, using memories and ideas creatively.

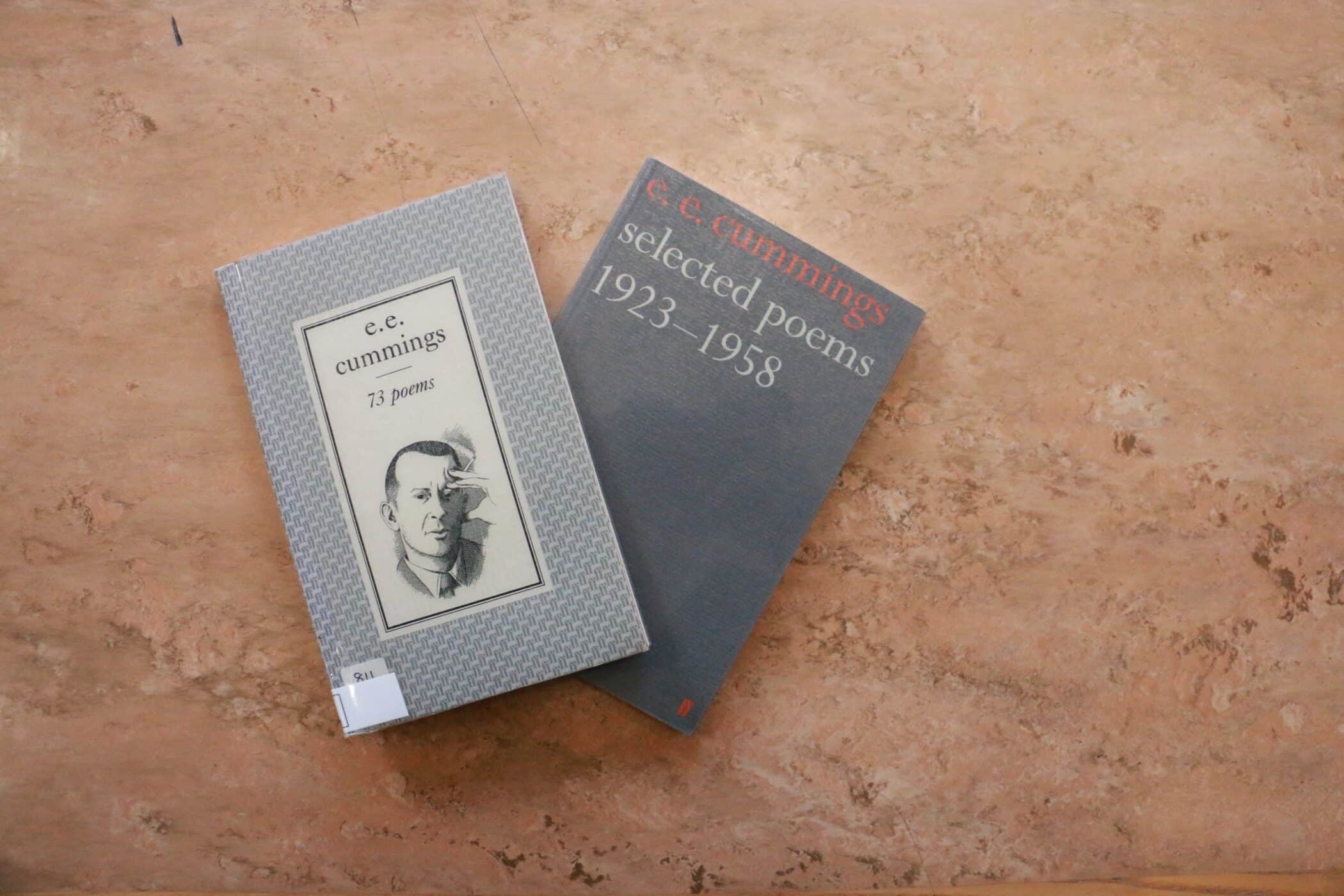

That thought prompts another. I think there is a particular type of creativity that is especially connected with dreams. Poetry and dreams share a common language. Perhaps that link is the reason that every human culture understands itself through poetry and song.

What is that common language? In poetry, we often describe one thing in terms of another. Shakespeare wrote, ‘All the world’s a stage…’ This is a metaphor. It is also an essential part of a dream. In your dreams, nothing is what it seems to be. Everything represents something else. Everything symbolises another thing. This is why dreams sometimes need interpretation. The essence of the things that make up your dream is that they serve as a metaphor for something else.

Another type of representation in a dream is described in poetry by the word metonymy. Metonomy is a figure of speech where one word or phrase is substituted with another that’s closely associated with it. Unlike metaphor, which draws symbolic comparisons, metonymy relies on real-world associations. For example, the phrase ‘The pen is mightier than the sword’, means communication, represented by a pen, is more powerful than conflict, represented by a sword. Similarly, the objects and people you dream of stand for other things. When something appears in your dream, the associations you connect with it allow you to explore something important to you through that dream.

A third element of poetry that is at the heart of dreaming is called synecdoche. This is a figure of speech where either a part represents the whole, for example using ‘wheels’ to describe a car, or where the whole represents a part, for example, ‘England won the match’ specifically means the English team. When you dream, you may often encounter objects that are a part of something else and stand in for it in your dream.

There is another key connection between dreams and poetry. In a dream, everything is about you. Sometimes people say to each other, ‘I had a dream and you were in it’, or ‘I had a dream about this or that thing.’ That is incorrect. In fact, you had a dream in which you explored something important to you, using the other person or other object as a symbol of that thing. You are everyone and everything in your dreams.

Similarly, in poetry, the point of the poem is not the subject of the poem. The poem is using that subject to explore something else – an emotion or idea important to the poet, or a chance to use language in a new way. Just like your dream is really all about you, regardless of what appears in it, so the poem is all about the poet, regardless of its subject.

So, I hope we have learned something in the course of this intellectual ramble through the world of sleep and dreams. Dreams are still as mysterious to us as they were to Hani, the Ancient Egyptian, over 4000 years ago. But we might have discovered some new thoughts about dreams.

How strange to think that this plastic device on my wrist, provides me with data on something so profound as sleep and dreams. The device is monitoring the seat of thought, the essence of personality and the root of creative expression.

Shakespeare was deeply interested in sleep and dreams; it is now surprise he has appeared several times in the course of this assembly. It seems appropriate to finish with him, as he often captures the centrality of dreams to our existence and identity. He does this best in what was probably his final play, The Tempest. Prospero, the magician whose magic animates the play, is thinking about life and mortality. He describes humans thus:

We are such stuff As dreams are made on, and our little life Is rounded with a sleep.

I would like to thank Yuvraj B. (U6th), Casper H. (U6th) and Ms Chakraborty, who helped me with this assembly by providing useful research.